Address Newsletter

Our weekly digest on buying, selling, and design, with expert advice and insider neighborhood knowledge.

New England’s aged housing stock has seen it all. Sometimes weathered floorboards and hand-smoothed bannisters tell a clear story. But now and then there are twists in the narrative, and after a 100 years or more, the structure may not resemble much of its original self.

“Almost every historic home has been ‘remodeled …’ said Walter Beebe-Center, president of Wilmington-based Essex Restoration. “Someone’s removed something that was just so gorgeous and beautiful. It’s a crime that it was thrown away, and others have added things that are so out of context.”

For those who purchase old homes, not all of their early aesthetics remain because of generations of updates. And whether embarking on a museum-quality historic journey or just adding back a few nostalgic touches, restoration after renovation can be a chance to revitalize lost character while making space for modern use.

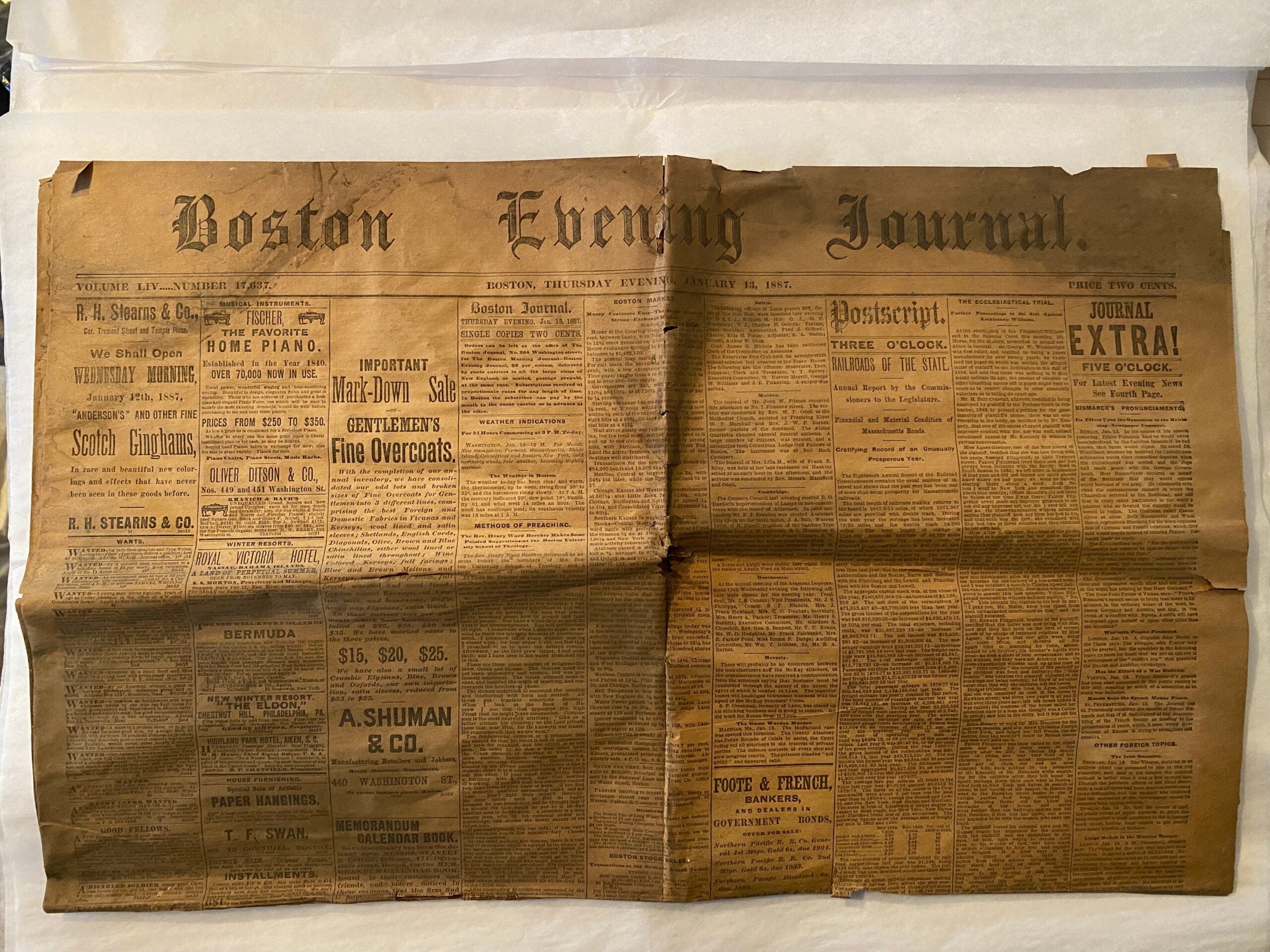

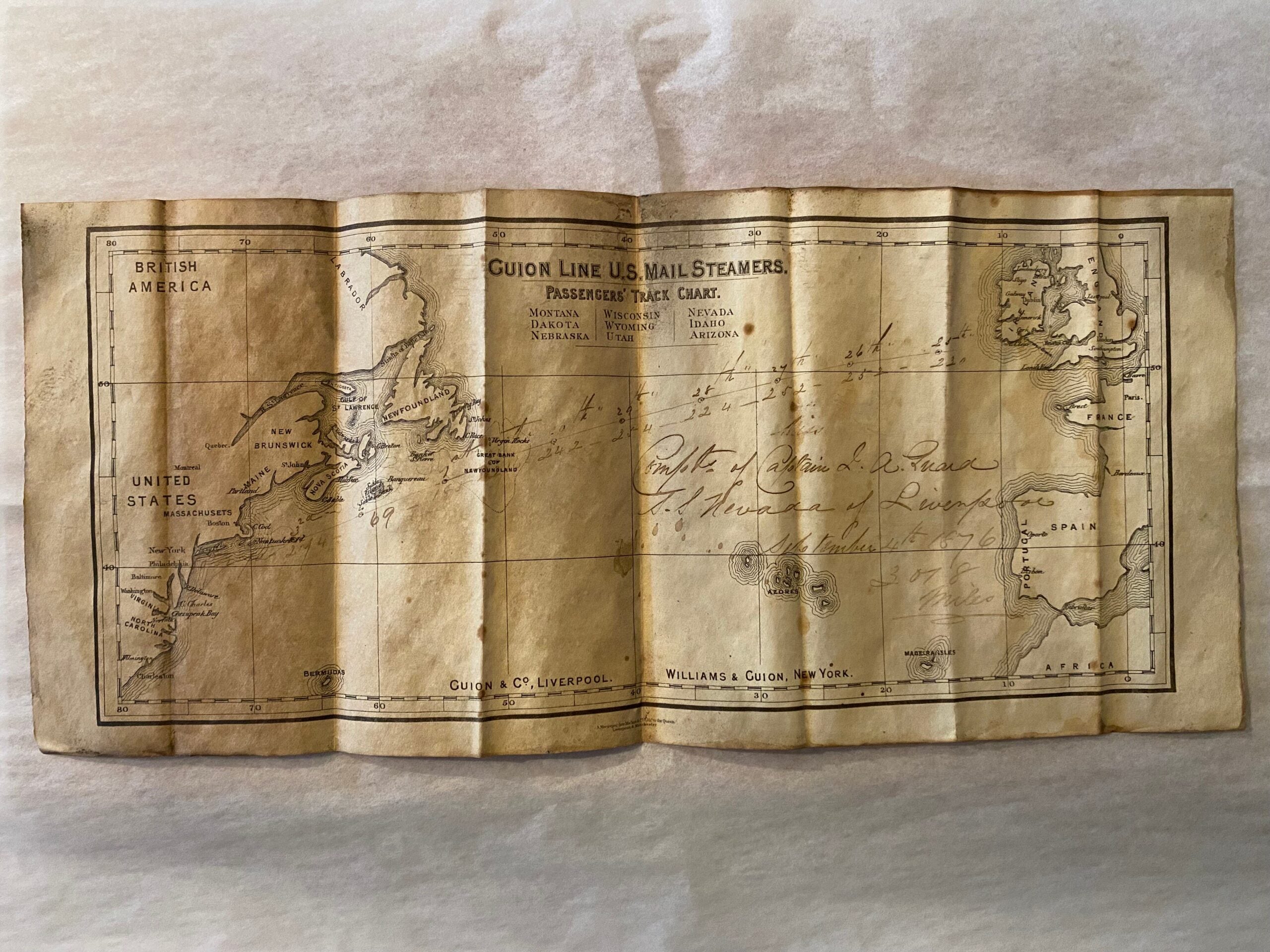

In West Medford, Sara Berndt has spent the past three years peeling back layers in her home that on record dates to 1910, possibly earlier according to some newspaper clippings she found. And while her early task list was based on essentials, her curiosity grew about what was underneath the green shag carpet and linoleum.

“I don’t really feel the need to put our touch on things,” said Berndt, 31. “I want to restore it to the way it was when it was built, and keep that legacy going.”

Following cumulative renovations by a long-term owner — Berndt’s folk Victorian home with Gothic influence was worked on in its later years by a handyman who improperly renovated a bathroom — or other factors, such as a quick flip, materials removed may be gone forever. Nathan Goodwin, a South Shore-based historic preservation carpenter, starts by researching what the home might have looked like.

“A lot of times people don’t appreciate that … and they just want to flip a house and make as much money as possible, so they just slap everything together,” said Goodwin. “But it’s a very thoughtful process.”

And while a house’s walls can’t talk, its current stewards are now tasked with speaking for it.

“You basically have to take it all out and start over again,” said Goodwin, who advised homeowners to start by researching what the house should look like, and why it was built as it was.

For Peter Smith, who directs North Bennet Street School’s preservation carpentry program in Boston, the process is something he calls “forensic carpentry.” Most people, he said, just aren’t trained to consider a historic home, and often assume it’s a tear-down. That’s just not true, he said.

“I go deeper into the ability to understand the built environment, and peel back layers to kind of read the historic fabric,” said Smith. “It’s a connection to the physical world that we only learn about in the textbooks.”

Not every original aspect of the home may remain relevant to modern uses, so as you begin a restoration project, Beebe-Center said that’s a good time to think about how you want it to work in addition to how you want it to look.

While museum restorations might consider moldings and other architectural details, home projects require other necessities: electricity, doorbells, and Wi-Fi, for example.

A formal dining room or tiny historical kitchen may not meet your modern needs, and that’s OK. Beebe-Center said the idea is to “blend” historic aesthetics with modern practical function. That could mean opening up a tiny kitchen while preserving a stately front parlor.

“[It’s] being informed both by what are the practical changes that are required for this house to be functional in the 21st century, and what are the aesthetic repercussions of what we’re thinking about doing, so that we can make the changes harmonious,” he said.

Finding period-appropriate materials and sometimes using older methods can take longer than many modern processes. Smith said it’s important to adjust timeline expectations, which quick-flip TV shows can often distort. For example, Smith sources lumber from local mills for historic timber frame construction as opposed to big-box stores.

Those trained to do the work are a smaller subset within the already sought-after carpentry world — Goodwin said he’s currently booking five years out.

Those who work on these old homes follow different criteria based on the goals and site, from historic preservation and conservation to rehabilitation and restoration. And it could include modern renovation along with some historic details. Smith, at work on a 1725 Hanover home restoration that had experienced several modifications through the years, described his project as incorporating multiple such categories of work. To define the project, considering which time in history will be referenced is an important notion.

“You’re creating a philosophy of refurbishment,” he said.

Refer to old photography and tour neighborhoods with similar period houses to find clues about colors or porch location, said Smith. Perhaps a bit of wallpaper turns up in a closet.

“My instinct is to let the house tell the story of the house and its transitions,” he said.

It can be a lot to consider, and to afford. Limit scope by focusing on just two rooms, or the facade. Starting with smaller details — moldings, door casings, and window trim, which provide historic quality — can be a good idea. And windows themselves are an often overlooked historic feature, and the most obvious style queue, said Smith.

“You have a window that lasted 150 years,” he said. “There is no reason not to expect it to last another 150 years when it’s restored appropriately.”

Marc Bagala restores and replicates historic windows in southern Maine, and said that irreplaceable 100-year-old pine is always reparable.

“They are a great quality wood, and we know they’ll last for another 100 years,’ said Bagala. “And being the snobby window restorers that we are, we know that they will outlast any replacement window that is being put out there on the earth right now.”

Starting with the finishes is an even lower-threshold to bring back historic character.

If it’s quick to pull out, it can be quick to replace, said Mike Thompson, owner of The Old House Parts Company in Kennebunk, Maine. He oversees more than 12,000 square feet of old handles, doorknobs, brackets, sinks, and just about any other trimming salvaged from very old homes. The collection stretches back to “as old as we can get,” said Thompson, noting especially plentiful stock dating to the housing boom in the 1890s and early 1900s. But if it’s cool and from the 1950s, Thompson said he won’t turn his head.

“It can be super simple things, like antique cast iron floor registers [after] someone stuck in crappy ’80s ones,” he said.

“Literally, they don’t make it like they used to,” said Thompson. “They made stuff to last forever, if it’s taken care of.”

Our weekly digest on buying, selling, and design, with expert advice and insider neighborhood knowledge.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Be civil. Be kind.

Read our full community guidelines.