Sign up for the Today newsletter

Get everything you need to know to start your day, delivered right to your inbox every morning.

By Annie Jonas

Harvard Yard is one of the most iconic spaces in American academia — not just for its ivy-covered buildings and criss-crossed walkways, but for the long tradition of activism that has played out in the space.

Since Harvard opened its doors in 1636, students and local residents alike have been challenging the university’s administration, voicing dissent, and shaping national conversation from the center of campus.

The latest has been the protests against Israel’s war in Gaza, which Timothy McCarthy, a social movements historian and a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, said reached levels of divisiveness to rival some of the campus’s most explosive protests.

“There was a different tenor and tone to the protest,” he said. “I have never seen the conflict on campus more divided than it was last year. It was just brutal.”

Harvard Yard has “always been sort of a quasi public space, even though it belonged to the university,” Beth Folsom, program manager at History Cambridge (formerly called the Cambridge Historical Society) told Boston.com.

Despite its location on campus grounds, in the 17th century Harvard Yard acted as a “cow yard,” not a gathering place for students, according to Daniel Berger-Jones, CEO and co-founder of Boston Historical Tours.

“It’s where they kept dinner,” he quipped, adding “It’s now, of course, where we keep the freshmen.”

The Butter Rebellion of 1766 was considered the first known student protest on an American campus, according to Berger-Jones. Students protested against the poor quality of food on campus by rioting in Harvard Yard and penning an epic to voice their qualms.

“Behold, our butter stinketh! – Give us, therefore, butter that stinketh not,” the poem read. The food-focused unrest continued with the Cabbage Rebellion of 1807, when maggots were discovered in a plate of cabbage.

In 1780, as the Revolutionary War was raging, students gathered in the Yard to demand the dismissal of then-Harvard President Samuel Langdon, who they believed to be too radical and too tied up economically and politically to the Revolution.

“He was the first Harvard college president to be popularly forced to resign,” Folsom said.

Protests cropped up in the decades that followed – against the Mexican-American War in the 1840s; against WWI and WWII, for example – but they didn’t reach a breaking point until the anti-Vietnam protests of the 1960s.

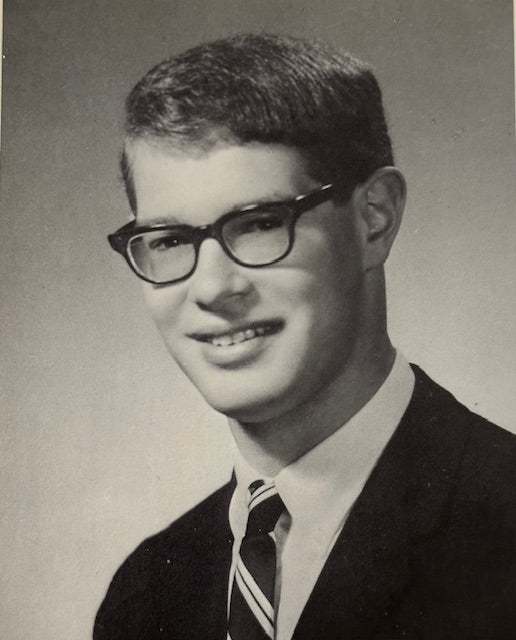

Harvard students like Robert Krim, Class of 1970, was a member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and one of the hundreds who took part in the University Hall takeover in April of 1969.

It started the night of April 8 when SDS pinned a list of demands for the university – like abolishing the school’s ROTC program, stopping university expansion into working class neighborhoods of Cambridge, and calling for the establishment of a Black studies program – to the door of Harvard University President Nathan M. Pusey’s home.

The next day, hundreds of students gathered in Harvard Yard and read the same list of demands to gathering protestors.

Crowds poured into University Hall and took over the building. Later, Pusey announced there would be police action to remove the students.

“That seemed fairly ominous,” Krim told Boston.com.

Police forcibly entered University Hall early on April 10, Krim said moving room by room to remove students.

“They had clubs and truncheons covered with rubber to beat people,” Krim said.

As students were dragged out, the brutality escalated. “People were pulled down from the stone steps into Harvard Yard and what was called the ‘hot box,’ where police wielded billy clubs, hitting the backs of heads. There was blood everywhere.”

Krim was arrested and used a phone call from jail to relay updates to the Washington Post, where he’d also been working as a correspondent. The student journalist, now 77, helped the world witness the brutal crackdown. “I went back to the Harvard Crimson offices, and we put out a special emergency edition,” he said.

According to a Harvard Crimson article published April 10, 1969 “between 250 and 300 people were arrested in the raid, and nearly 75 students were injured.”

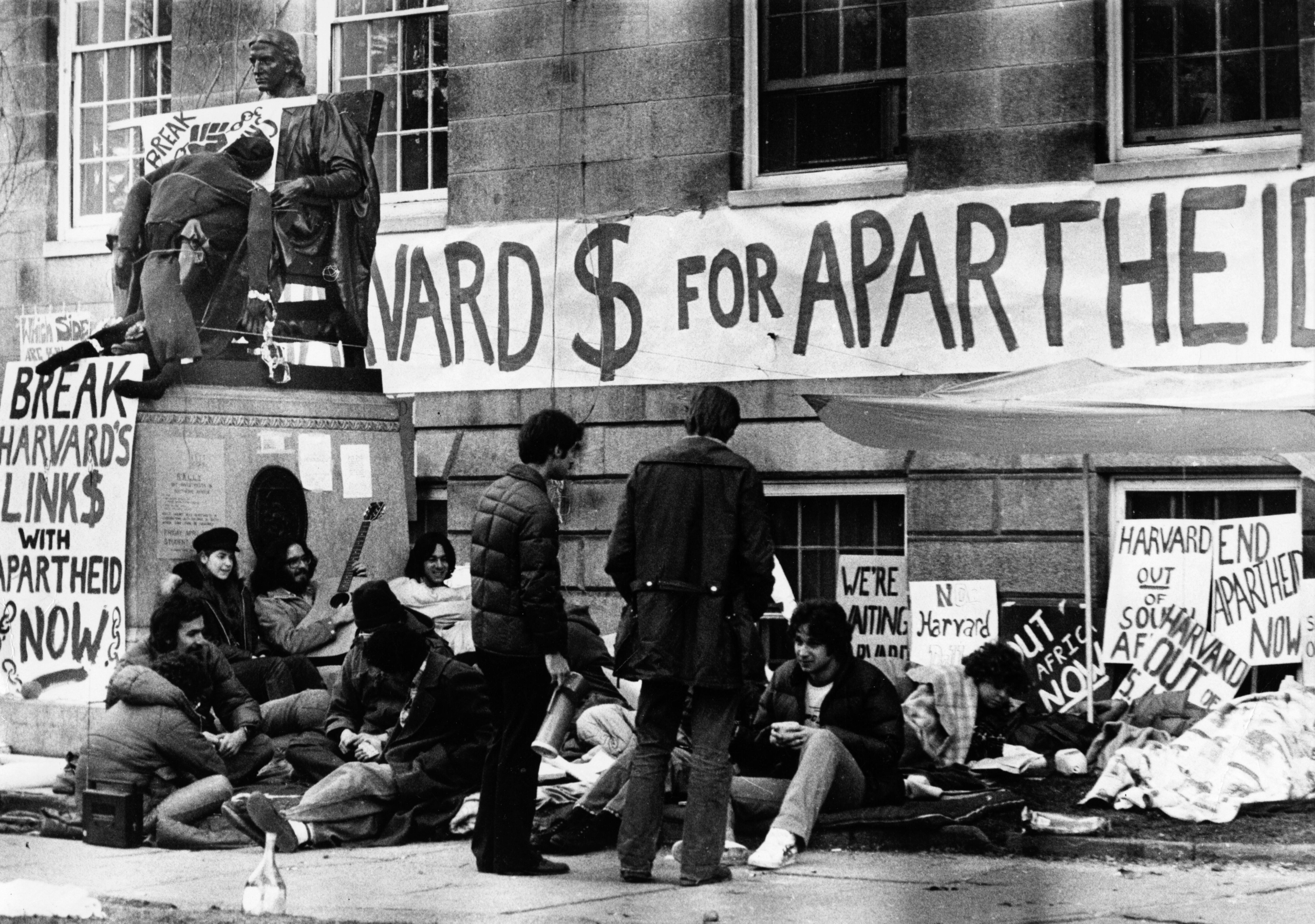

Harvard students went on to mobilize in the Yard around apartheid in South Africa in the late 1970s, LGBTQ+ rights in the 1980s, a living wage in the late 90s, and more.

The centuries of protest at Harvard Yard have a cumulative, symbolic effect on the physical space, McCarthy said – as if the Yard’s protest history has become baked into the physical space, giving more punch to current protests.

“The built environment at Harvard Yard and the kind of histories that these buildings represent are often part of the protests themselves. I think students are quite smart to make use of them.”

Annie Jonas is a Community writer at Boston.com. She was previously a local editor at Patch and a freelancer at the Financial Times.

Get everything you need to know to start your day, delivered right to your inbox every morning.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com